Turn of the Card, v3.4.3

Get the game!

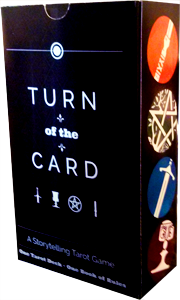

Turn of the Card: Essential Black Box is now available for sale at TheGameCrafter.com. The set includes a beautifully illustrated 78-card deck, the complete core rules, and two reference cards. It's everything you need to go to Mars, negotiate with dragons, or chase shadows down a dark alley. Pick up your copy at TheGameCrafter.com!

Creators:

Paul Abeyta and Jefferson Lee

Chief Agitator:

Mark Rybus

With thanks to:

Adriel Algiene, Jeremy Alva, Alice Baker, Cynthia Calongne, Megan K. Eberhardt Frank, Sean Frank, Kristin J. Higley, Brian Hughes, Lee Langston, Lori Langston, Khiri Samantha Lee, The Lucreative Group (Class of 2015), Theresa Pridemore, Bjorn Oswalt, Wen Reischl, Oliver Rose, Michael Strickland, Paula Strickland, and also Andy, Ava, Billy, Dave. Kris, and Lindee

Talk to us on Facebook! // Got an eBook? Download the FREE .pdf eBook! // Need character sheets? Download a character sheet!!! // P.S. Get the game from TheGameCrafter.com!

And hey, Copyright ©2016, Paul Abeyta and Jefferson Lee.

0.0 Introduction

Turn of the Card is a storytelling game which uses a deck of Tarot cards and the collective imaginations of you and your friends. During the course of the game you will weave a tale through the actions and choices of characters that you will create, in scenes that you will help to shape and setup.

There are no limits to the sorts of stories that you can tell with this game, and we hope you enjoy getting to explore all of these possibilities.

0.1 Collaborative Storytelling

In Turn of the Card the participants share the responsibility of telling the story. There are two main roles in this game: the Players and the Narrator.

The Players

The player is the driving force of the game. Each player creates and assumes the role of one of the main characters. She plays the game from the perspective of her character, narrating each of their actions according to the strengths, weaknesses, and motivations chosen for this character. These choices help guide the plot, and move the story forward.

The Narrator

There is only one Narrator and she acts on behalf of the story, deciding how it will react to the actions of players’ characters. These choices help to set the tone and frame the scenes that the characters inhabit. She creates the enemies the players’ earn after their triumphs or mistakes, she plans out the secret conspiracies encircling the characters, and the natural disasters that come out of nowhere. The Narrator gives life to the world the players’ characters exist, and gives those characters the motivation push the story forward.

The Narrator also acts as a facilitator, deciding how the game should proceed when the rules do not provide a clear answer. The the game provides some balance and structure, but it cannot account for every possibility, so there will be disputes and issues that can only be resolved by the Narrator.

The Collaboration

What makes this game unique to traditional storytelling is that the main characters are constantly making their own paths through the game. The players are confined to the perspectives and abilities of their characters, but they are free to push those characters to their limits and can change the course of a plot in truly memorable and fantastic ways. The Narrator, on the other hand, will never know exactly what the protagonists plan to do next, but she can still fill their world with thrilling surprises and clever twists, drawing them deeper and deeper into the story. Everyone in the game shares the joy of both telling a good story and watching that story unfold, and that collaboration is what makes this game fun.

0.2 The Tone

These rules are written with a more modern tone, but you and your friends are free to tell whatever story you want, even if that means changing some of the rules. If your story involves 14th century piracy, swap electronic skills for sailing. If there are vampires in your story, give them a supernatural edge over their mortal prey. And when your stories end up in the interstellar void of deep space, make sure your characters are outfitted with dual-phasic gravitonic Talson-Mayner emitters to prevent Tachyon shifting. The rules are only here to give the game some balance and structure, and they should never hold you back from expressing the kind of tale you want to explore.

1.0 The Characters

Creating characters is the first step to playing the game. For the players, their character is the sole conduit to the story. They will explore the game through the perspective of this character, and make choices that reflect the experiences of the character, which might not be the same experiences as the player. The kind of character a player creates determines how she will play the game.

Non-Player Characters

Non-player characters (NPCs), are characters that are created by the Narrator, and they act as her conduits to the story. Unlike players, Narrators are not attached to just one character, and she might create a wide cast of NPCs, ranging from major antagonists to minor background characters, to support the plot.

Since a Narrator is responsible for so many characters, she will not always have fully developed NPCs. A major villain might have a long history and a list of abilities more impressive than the players’ characters, but the villain’s faceless minions might not be much more than outlines with enough detail to fill out a scene or act as a nameless obstacle for the players’ characters.

1.1 Meet Mia Jones

To help you better understand the rules, we will follow the story of Mia Jones. We will use Mia in all the examples in this book, but for now we will get to the business of creating Mia.

1.2 The Concept

This is the hard part: what kind of character are you creating? It’s the hardest because it’s meant to set you up for everything else. A concept can come from a wide variety of inspiration, but here are some sample questions you could answer:

- What inspires, motivates, or drives your character?

Mia is both ambitious and adventurous, so while she wants to achieve unmatched success, she wants to do it in the most exciting way possible.

- How have your character’s motives shaped her life?

Mia has never been a child of convention. While it was abundantly clear that she was an extremely talented child, she never succeeded at school, which bothered her greatly. She dropped out of public education as soon as it was possible and took her education into her own hands. Mia excelled at the paths she chose, until finally finding her calling as a very successful stunt driver.

- What does your character have planned for her future?

Mia has been a stunt driver for four years and while she still loves to drive, things are starting to get boring at work. Complacency has always been Mia’s greatest fear, so she’s decided to start finding “unconventional” work.

- What obstacles will your character have to overcome?

Ultimately, Mia’s constant enemy is her unyielding ambitions. She is relentlessly pursuing the next great adventure, driving herself right to the razor’s edge of catastrophe. She has never failed, which only makes her more dangerous.

The Narrator’s Input

The Narrator should have an active hand in character creation, especially while the players are generating concepts, because a player’s character might not fit the story the Narrator has prepared. A character who brings joy and cheer to children in hospitals will have a hard time fitting in a plot involving deep political intrigue and corporate espionage. The players will not know all the details of a story, so having input from the Narrator is essential for creating characters that will match the tone and are going to be fun for a player to explore.

1.3 The Fine Details

After you establish your concept, you’ll want to work out the other details of your character like name, age, gender identification, and appearance. You will probably add more details to your character as she grows, so you only have to focus on the immediate details that would come up during an introduction.

Mia Jones is a Peruvian-American woman with a strong, fit build, and extremely short hair. It is supposed to be a buzz cut, but she usually lets it get shaggy before cutting it back down. By the time she starts looking for underground work, she is 28 years old.

She has one brother living in the city, while her mother and father live in Colorado, far enough away that they can only meddle by phone.

1.4 Traits and Aptitudes

Your character’s Traits and Aptitudes help define her capabilities and her limits.

Traits

Traits define what your character can do, but in broad terms; they’ll point you to the obvious, but you’ve got some room for interpretation.

Mia mainly uses her Driving trait to drive, but she also uses it to plan getaway routes, pick the right cars for heists, and find fantastic deals at the police county auction.

You don’t have to stick to the obvious -- don’t be afraid to get creative with how you use your character’s traits.

Aptitudes

Aptitudes, on the other hand, are very specific. They’ll tell you exactly how well a character performs in a given trait.

Mia is Great at Driving which is how she paid for her house in cash. Meanwhile, Mia’s brother is Poor at Driving so he usually takes public transportation or waits for Mia.

There are the nine main aptitudes:

|

PeerlessThe PinnacleThe kind of ability defines a legend and can alter the course of history. |

|

IncredibleThe MasterA profound and deeply intuitive mastery over a gift which can tilt the world stage. |

|

ExceptionalThe SpecialistInfamous talents that are coveted and highly sought after. Commands both fear and respect. |

|

GreatThe Grizzled VeteranHeroic talent that saves the day and tilts the balance. This is the highest level most people achieve. |

|

GoodThe Seasoned ProfessionalExpert capabilities built on constant practice and diverse experiences. This is enough skill to tackle most challenges. |

|

FairThe Fresh RecruitNot enough experience to be respected as a professional, but enough skill to get the job done, with some instruction. |

|

MediocreThe EverymanBaseline survival dredged from public education, the Internet, and pop culture. |

|

PoorThe Hopelessly IneptEnough ability to be almost mediocre. |

|

DismalThe Bumbling FoolZero talent that flirts with disaster. |

1.5 Picking Your Traits

You get ten points to spend on your character, with the following guidelines:

- Each rank above Mediocre costs one point, so a Great trait costs three points.

- You cannot start with any trait better than Great.

- You cannot start with any trait worse than Mediocre.

Mia was born to drive, so she is Great at Driving, and it helps that she has Good Reaction. Her courage and determination, give her a Good Grit, and because she tries her best to stay fit, she’s got Fair Health. She has not been an underground figure for very long, but she is a fast learner, so she’s picked up Fair Manipulation and Fair Underground.

The Traits List

We have put together a big list of traits, but by no means is it complete. The traits listed here are the most common traits for a modern game, but if you do not see a trait that your character would possess, you and the Narrator are free to define a new trait and add it to this list.

You might also want to alter this list if you and your group decide to play in a setting outside of twenty-first century Earth. Pirates really have no need the Hacking trait, while time travelers from Mars could consider Firearms training quite quaint.

Requires Specialization

Some traits require a specialization, which means you must choose a specific focus for this trait. For example, Academics requires you to name a school of study, like Academics: Biology, or Academics: Russian History.

Core Traits

We highlight the core traits in our list because they are important in determining what happens to your character in a fight and when she is dealing with trauma. They can be used just like any other trait, but they have a special significance in this game. There are three core traits: Brawn, Health, and Reaction.

| Trait | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| Academics | Requires specialization. The study and knowledge of an academic topic. | |

| Allure | Not just the looks, but the entire art of seduction. | |

| Athletics | General physical capabilities. | |

| Brawn | Core trait. Brute strength and ability to deal with pain. | |

| Connections | Finding the right people and getting the right resources. | |

| Demolition | The skill required to handle explosive ordnance and weapons. | |

| Driving | Specifically automobiles. | |

| Engineer | Requires specialization. The ability to assemble and repair complex technical systems. | |

| Firearms | Shooting guns. | |

| Grit | The determination to stay in control, no matter what. | |

| Hacking | Outsmarting digital security, mostly through human error. | |

| Hand Weapons | Blades and clubs bigger than a machete. | |

| Health | Core trait. How much damage you can take before dying and general well-being. | |

| Interrogation | Getting to the truth with mind games or fists. | |

| Intimidation | The ability to be absolutely fucking scary. | |

| Jury Rigging | Making repairs when you don’t have the right parts. | |

| Leadership | Maintaining order even if you have no idea what you are doing. | |

| Manipulation | Control via lies, leverage, or empty hope. | |

| Medical | Keeping the blood inside the body. | |

| Melee | Fists and anything smaller than a machete. | |

| Psychology | Getting into someone’s head, and making some kind of sense with that mess. | |

| Reaction | Core trait. How fast you can draw a gun, or dodge a bullet. | |

| Security | Bypassing physical security, like alarms and locks. | |

| Senses | Eyes, ears, nose, touch, and sometimes taste. | |

| Stealth | Avoiding senses, and sometimes taste? | |

| Survival | Foraging, hunting, and thriving in the wilderness. | |

| Underground | Just like Connections, but add “illegally”. |

1.6 Creating NPCs

It is up to the Narrator to create the NPCs for the story. Although creating characters can be easy, the Narrator do not have to go through all of these steps for each of her characters. The major figures in a story should be as developed as any of the players’ characters, but the rest can simply be a job title, possibly a name, and a single distinguishing trait.

While the Narrator has spent a lot of time thinking about the motivations and capabilities of Mia’s new employer, the Triad boss Mr. Chow, the character that will be assigning Mia her jobs is only known as Franklin and he has a Good trait in Underground.

As the player characters progress, so will the NPCs. Even very minor characters can grow and become pivotal actors in a plot, revealing new details and traits as the story continues.

While Mia had a hard time trusting Franklin Weldt at first, they have forged a close friendship has saved both of their lives. Though Mia always asks if he wants to join her on the jobs, he prefers to stay at the garage repairing cars (Good Engineering: Automotives) and keep up to date with global politics.

2.0 Core Rules

2.1 The Tarot

The Tarot is used in this game for the same reasons it is used traditionally: to act as a guide when the outcome is uncertain. The course through a game will not always be clear, and while it is ultimately up to the Narrator to decide what happens next, the cards lying on the table can help influence her decision, though some cards will give the players the opportunity to exercise much more control over the destiny of their characters.

They way these cards are interpreted will be explained in more detail later, but here are the ground rules:

1. First Hand

At the start of every game, the Narrator shuffles the deck and passes out five cards to each player, including herself.

2. Getting New Cards

You have to play all of the cards in your hand before you can draw new cards, and you cannot discard any card without playing it first. You have to find a use for each of your current cards before you get new ones.

3. Wear and Tear

Each time you draw a new hand, your hand size is reduced by one. So if a player finishes her first hand of five cards, her new hand will only be four cards. It is possible to have a hand size of zero cards.

4. Narrator’s Advantage

The Narrator can always choose to draw up to five cards per hand if she wishes, but she must still use up all of her cards in order to draw a new hand.

5. Recycling

If the deck ever runs out of cards, shuffle up the discards to make a new deck.

2.2 Trait Checks

Your character is one of the main characters of the story, so she is extremely capable and will succeed at most tasks she attempts (unless they are impossible). However, from time to time, your character might try to do something risky enough to put the outcome of her actions in doubt. In these cases the Narrator will check your character’s traits.

When the Narrator checks, she must choose a relevant trait and decide the outcome based on your character’s aptitude in that trait. The Narrator is not required to tell you what trait she will be checking. If the Narrator doesn’t see a relevant trait, your character will be relying on a Mediocre aptitude.

Mia is Great at Driving, so when she quietly evades the police on a route that she knows intimately, the Narrator doesn’t bother with checking her traits. However, when she tries prying open a security door, the Narrator asks to look at her traits to check her Brawn trait.

2.3 The Push

If you are not sure that your character’s aptitudes are enough to match her ambitions (or you just want to hedge your bets), you might want to spend some of your cards on a push.

Pushing gives you the opportunity to affect the outcome of a check by playing cards to boost your aptitude. Pushing is a gamble because you will not always know what trait is being checked, or how far you need to push your aptitude, but this is the last chance you get to influence the Narrator’s decision.

Even with a crowbar, Mia doesn’t think that she has the strength to open this door (Mediocre Brawn), so she opts to push. The Narrator nods quietly and in her head she notes that Mia will need Great Brawn to get past the door.

If you decide to push, there are four steps to follow.

1. Pick the Push

You need to decide whether your character pushes herself physically, mentally, or socially, and narrate how that choice applies to your character’s actions. The type of push you choose is important because it determines the suit of the push.

- Physical pushes wield Swords.

- Mental pushes focus on Wands.

- Social pushes carry Cups.

Only cards that match the suit of your push will have an effect on your character’s aptitude. You can play cards that do not match this suit, but they have a different effect on a push.

The Suit of Pentacles

Pentacles represent the wild forces of fate and will always have an effect on your character’s aptitudes, regardless of the suit of the push.

Creative Pushes

You don’t have to pick the most obvious choice for a push, as long as your story makes sense. A driver pushing for the finish line can choose to use Wands to stay mentally focused on the road, Swords to maintain physical control over the wheel, or Cups to fuel her overwhelming desire to humiliate her sexist opponents. In most cases it is more important to tell a good story than to pick the most favorable suit.

Mia is only carrying Wands and Cups, so she decides to take the logical route. Mia closely scrutinizes the door and her surroundings, trying to find a way to leverage her strength, instead of blindly bashing away at the steel frame.

The Narrator’s Pick

If the type of push needed for a scene is unclear, or a player chooses a push that seems inappropriate, the Narrator can change the suit of a push. This option should only be used if a suit is clearly mismatched, or if the player really cannot give a good reason for picking the suit.

Alternate Decks

Turn of the Card works with any Tarot deck, but the suits might be named different than the ones listed in this game. The most common difference is that the suit of Pentacles might be substituted with the suit of Coins. Ultimately, if your group decides to use a different deck, be sure to decide what each suit represents before starting the game.

2. Play the Cards

You can play as many cards as you want from your hand. Place them face-down to show you mean business, and when you are done playing your cards tell the Narrator that you are ready for the reveal.

If Mia fails, she won’t be able to get past the door, but at least she won’t be in trouble (probably). She decides to play two cards: the only Wand in her hand, and a Cup card.

3. Reveal the Cards

Once you reveal your cards you cannot put any more cards into play. When you are fully committed to your cards, flip them over to find out what happens to your character:

- Add one rank to your trait’s aptitude for each Pip card (the numbered cards, one through ten) that matches the suit of the push or is a Pentacle.

- Add two ranks to your trait’s aptitude for each Royal card (Knave, Knight, Queen, or King) that matches the suit of the push or is a Pentacle.

- Cards that do not match the suit of the push are Burned.

- Major Arcana go rogue and play by their own set of rules, which are detailed below.

When the cards are revealed, Mia’s Brawn is boosted to Fair from her Wand card, but her Cups card is going towards a burn. Mia is definitely worried that Fair isn’t going to be enough to get the job done.

Burned Cards

Sometimes you won’t have the right cards in your hand, which is why burning is an option. When you choose to burn a card, draw a card from the deck for each card burned, and play it face up on the table. If the card matches the suit of the push, is a Pentacle, or is a Major Arcana, you get the bump; everything else is discarded without any effect.

Since she is only burning one card, Mia draws one card from the top of the deck, revealing the Star Major Arcana card.

The Major Arcana

The Major Arcana are the most powerful cards in the deck. They do not have a suit and can be used in any push. If a Major Arcana is revealed, the character succeeds critically, regardless of her aptitude. You only need one Major Arcana to succeed critically, but if a couple show up (which might happen while burning cards) you get to pick which one to use. This is different in contests where multiple Major Arcanas carries a bigger advantage.

Anytime a Major Arcana shows up you have a choice: you can turn the card towards yourself or towards the Narrator.

...Toward You

If you point the card in your direction, you get to decide the final outcome of the push, but you must base your narration on the symbolism of the card in play. You can be literal, symbolic, or work from the traditional interpretations of the Tarot, but the card must make a significant appearance in your scene.

It is important to remember that this is your scene now, and while the Narrator might make some adjustments to help it fit the story, you get total control over what happens as a result of your push, as long as it is possible for your character. The Major Arcana puts a spotlight on your character for the chance to do something heroic, not impossible.

No matter how hard Mia tries, she can’t pry open the door. In her frustration, Mia resorts to simply glaring, and without warning, the door flies open and Franklin steps through the opening. Stunned, Mia barely recognizes that Franklin is frantically waving for her to come inside. She drops the crowbar and dashes in before the door slams shut. The night becomes quiet again, and high above, Scorpio glows a little more brightly. It is the constellation of stars that Mia and Franklin have shared since birth, and it now acts to draw together their two destinies.

...Toward the Narrator

Of course, it is not always easy to come up with something that fits the card, so if your mind goes blank you can always turn the card toward the Narrator.

Your character still critically succeeds in what she was intending to do, but the Narrator can add side-effects, caveats, or quietly start the clock on something that might be inconvenient later in your character’s story. Whatever the case, the Narrator must still include the card in her narration in some significant way.

Tonight the stars decide that Mia has just enough strength to pry apart the lock. As the door rattles open, Mia quickly slips inside and lets the door swing shut, failing to notice that she has also damaged the electronic lock on the inside of the door. Somewhere else in the building a lone light flickers in the dark, warning the guards that there might be a slight malfunction in one of the outside doors...

The Narrator’s Cut

If necessary, the Narrator can alter the player’s narration so that it fits in the framework of the story. This might happen if there are secret details that need to work with the player scene or if a player stretches too far past the limits of her character.

4. The Outcome

Unless a Major Arcana was revealed, the Narrator gets to decide the outcome of your character’s actions based on her adjusted aptitude score.

Once the outcome has been determined all of the cards on the table are discarded and your character’s aptitudes return to normal. If you are out of cards, you can draw a new hand.

2.4 Contests

Unless you are being very sneaky, or playing it very safe, your character will come into conflict with somebody who means to do them harm, at which point you will have the opportunity to contest their actions. Contests follow a flow that is similar to pushing, but there are some differences.

The flames start to gut the inside of the warehouse, and Mia tries her best to stay on her feet. Mr. Chow is dead, but his asshole of a son, David Chow, has her dead to rights and in the sights of his pistol. Still, all things considered, Mia thinks it’s been an okay night.

1. Setting the Stage

Every player involved with the contest gets the chance to narrate their character’s action, while the Narrator checks all appropriate traits, defaulting to Mediocre when a character does not have the necessary trait.

The player that started the contest narrates first, followed by everyone else in the order of their actions; though the Narrator can change the order if it suits the story.

Mia arm feels like a lead weight as she draws her gun and tries to center its sights on David. Mia is Mediocre with Firearms, so her gun sways wildly, on and off target.

David is Incredible at Firearms, and as Mia clumsily swings her gun towards David, he sends a single round towards Mia’s heart.

2. Pick a Suit and Play Your Cards

After setting up the scene, each player declares what suit they will be using for the contest, following the same guidelines use for a push. Once everyone has declared what suit they will be using, everyone plays their cards by placing them face-down on the table. Once everyone is committed to the cards they are playing, the contest can proceed.

Mia knows she needs to push her Firearms trait. She picks Cups as her suit, since this duel is about more than just life and death; if she wins she will gain a social standing she could never imagine.

She puts down her last remaining Cups card and both her Wand and Sword cards for a burn. Mia is going all out for this shot.

The Narrator and Contests

Since the Narrator might be juggling multiple characters, she can choose to play cards for each of the characters she has in a contest. The Narrator is still limited by the number of cards in her hand, so she must decide how to best utilize these cards: spread them out across all the characters, or concentrate on boosting a handful of characters.

David decides to pick Swords for this contest, opting to beat Mia on physical reflex, but this is a big moment for David, so he plays The Devil Major Arcana face-down to guarantee vengeance for his father.

3. The Reveal

When everyone is committed to their cards, everyone reveals their cards one at a time in the order established in Setting the Stage, and tallies their aptitudes. Cards are burned at this point, so unanticipated Major Arcanas might be revealed from the deck and shift the balance of the contest.

The Major Arcana

When a Major Arcana shows up at the table the player still has to decide: toward herself or toward the Narrator.

A Major Arcana always trumps any number of Minor Arcana and any level of aptitude. A player cannot withdraw cards she has committed to play or play extra cards; it is all part of the gamble of entering into a contest.

Major Arcana are resolved one at a time, in the same order they are revealed, until everyone gets the chance to resolve their card. Any player that has committed multiple Major Arcana must wait until everyone gets the chance to resolve their first Major Arcana before resolving the rest. The contest ends when there are no unresolved Major Arcana left on the table.

Mia’s heart sinks when the cards are revealed. Even if Mia manages to draw two Royal Cups during her burn, she cannot beat The Devil. Mia crosses her fingers and draws two cards for her burn. All of her good Karma finally pays off and she pulls two Major Arcana: Death, and The Hanged Man.

Mia pulls the trigger during her wild aim, and while her shot is sloppy, it’s good enough for Death to find its way.

Unfortunately, the Devil protects his own, and while David deserves to die today, Mia’s gun jams, sabotaged by an unearthly hand. Yet, in the fury, one shot rings true: Mia feels a searing hot pain racing out from her chest, shattering every end of her body.

Mia knows she is a dead woman now, hanged and waiting for her own Pale Rider, but even the dead are allowed a few parting words: “Thanks Franklin.” David is stunned when he hears the shotgun blast, but the surprise only lasts half a second before he slumps to the ground. Mia smiles wryly before collapsing herself. In the end we all fall to the hangman, and today he gets to string up two more souls.

Stalemates

Sometimes a contest ends in a draw. What happens in a stalemate is decided by the Narrator, but as general rule, a stalemate should result in no significant changes to the plot. That usually means that the defenders win ties, but we’ll leave that to the Narrator to decide.

4. Wrap Party

If no Major Arcana show up, the Narrator wraps up the contest by narrating the mayhem that ensues. When the outcome is finalized, clear the table and discard everything in play. Players may draw up a new hand if necessary, and all aptitudes return to normal.

Since Mia is now out of cards, she draws a new hand. Mia has been extremely busy, so she draws only draws two cards: a pair of Cups.

3.0 Combat

No matter how hard your character tries, there is still the chance that someone will want to start a conversation with fists, knives, or bullets. This section explains what happens to your character in this event.

3.1 Reaction Rounds

Fights are broken up into Reaction rounds, which determine the order of combat. The characters get to act according to their Reaction trait, though players can push to take an action sooner.

The characters with the best Reactions get to go in the first round. Actions that take place in a round are considered to occur simultaneously, even if they have to resolve their pushes or contests separately.

The characters that don’t get to act in this round are still able to defend themselves, but only if it is possible to defend against the attack.

When everyone that can act in a round has taken their turn, a new round starts with the characters that have the next highest Reactions. The rounds continue until everyone has acted or there is nothing left to resolve.

3.2 Combat Contests

Like any other conflict in the game, combat is resolved through a series of contests, with an attacker initiating the contest, and a defender trying their best to stay alive.

It is still up to the Narrator to decide what traits are going to be checked during a combat contest, but here are some general guidelines to help streamline a combat scene:

- Gun fight: an attacker’s Firearm trait versus the defender’s Reaction trait (to dive out of the way and possibly into cover).

- Sword fight: an attacker’s Hand Weapons trait versus the defender’s Hand Weapon or Melee trait (whichever is better).

- Fist fight: an Attacker’s Brawn or Melee trait (her choice) versus the Defender’s Brawn or Melee trait (by preference).

Overwhelming Odds

If a defender is facing more than one attacker, she takes a one rank penalty for each additional attacker she is facing. This penalty is applied to every contest she makes while defending herself, so a character facing down three shooters would suffer a two rank penalty against her Reaction trait for all three shooters.

This also applies in the reverse: an attacker trying to hit three targets will suffer a two rank penalty in all three contests against the defenders.

4.0 Trauma

When your character suffers physical trauma, the result is exactly what you would expect: crippled limbs become useless, blood loss ruins concentration, and pain consumes your character in ways that are uniquely horrifying.

There is a little bit of bookkeeping in this game to help you keep track of your character’s trauma, but it is vitally important to remember that your character never experiences trauma as points ticking down. To your character, trauma is physical terror and it has an enormous impact on her story. When your character experiences the shock of a bullet, a blade, or a fist, its influence should be felt in every action or decision that she makes next.

4.1 The Bookkeeping

If your character takes a hit, she will collect Wounds. Most weapons will list how many Wounds they inflict, though the Narrator can make some adjustments: a bullet to the chest is much more traumatic than a glancing shot across the arm. If a character takes a hit from something that does not normally have a Wound value the Narrator will assign a number.

Each Wound your character gains reduces all of her traits by one rank. If your character has two Wounds, her Great traits are now Fair, and her Mediocre traits are now Dismal. Your traits can go below Dismal, so keep track of every Wound.

Mia has endured a 9mm round through the chest, but not through the heart or spine. A pistol normally does two wounds but since it’s very nearly a fatal shot, the Narrator gives her three wounds. Mia normally has Fair Health, so she has now been ground down to Dismal Health.

4.2 Wounds and the Push

You always have the option to push whenever your character is about to suffer trauma. The same rules for pushing still apply, but instead of gaining ranks in a trait, you would reduce the number of Wounds that will be inflicted on your character. Playing a Major Arcana will stop all Wounds from an attack, even if you have to turn it towards the Narrator.

4.3 Dying

Your character cannot endure more Wounds than ranks of Health. For a character with Mediocre Health, that’s just three Wounds. If she falls below her limit, her organs start to fail and she won’t last long without immediate and extensive medical intervention.

Since Mia has Fair Health, she can endure up to four Wounds. Since she has only suffered three Wounds, her organs have not yet failed, and that gives Franklin enough time to take her to a surgeon that won’t ask too many questions.

4.4 Bleeding Out (Optional Rule)

As long as your character carries Wounds, the Narrator can inflict one Wound on your character to reflect her deteriorating health. You can still push to negate this Wound, but your character will eventually need medical attention. How often your character suffers a Wound from bleeding depends entirely on the Narrator, but the general rule is once every hour.

Stabilizing Trauma

The only way to stop bleeding is to receive medical attention. The care from a well stocked hospital is enough for most patients, but if hospitalization is not an option, a sufficient Medical trait will work. Each Wound a character carries increases the required Medical aptitude by one rank, starting from Mediocre. So a character with one Wound can only be stabilized by someone with a Fair Medical trait. This is just like any other check, so the person administering aid is free to push.

Franklin manages to get to a unlicensed doctor before Mia bleeds out, but she still has three wounds, which means that her doctor needs to have a Great Medical trait. Luckily, her physician used to be a renowned PHD before being busted for insider trading, so his Medical aptitude is Exceptional. Mia survives her trauma and starts the long process of healing.

4.5 The Magic of Armor

Each piece of armor has a rating that tells you how many Wounds it will stop. When a piece of armor with a rating of eight is hit with a weapon that does five Wounds, your character will not suffer any trauma.

However, each time a piece of armor soaks up a hit, subtract one from the rating of the armor. In the example above, even though your character suffers zero Wounds, her armor rating drops to seven.

4.6 Stun Damage

Any weapon that stuns has an attached aptitude score. When your character is hit with a stunning weapon, her Brawn trait must beat the strength of the stun (a tie is not good enough). You can push, but if you fail, the attack severely dazes and incapacitates your character for a few minutes. She might still be conscious, but the world is just a haze of light and white noise.

Some weapons (like explosives) will both stun and inflict Wounds, and each effect is treated separately. These weapons are very dangerous.

4.7 Healing

Healing Wounds can almost be as traumatic as receiving Wounds. Pain can linger for a long time after, and some wounds will never completely heal. It can also take a considerable amount of time to heal, but exact duration varies wildly. The very basic rule is that it takes about one full week to heal one Wound, but the Narrator can adjust that number depending on the severity of the trauma and the quality of a character’s recovery.

Normally three wounds would require three weeks in the hospital, but since these were critical wounds, and Mia is not recovering at a hospital, Mia is stuck in her bed for eight weeks, which is the longest vacation that she has ever taken.

5.0 The Gear

5.1 Guns, Knives, and Sticks

Below is a sample list of weapons that a Narrator can use as a reference point. There are a few new terms that we will need to explain:

- #Wn is an abbreviation for the number of Wounds this weapon causes. 5Wn means the weapon inflicts five Wounds.

- @ #m tells you the effective range of a firearm or other projectile weapon. If you try shooting past this number, the weapon only inflicts half its normal damage. The maximum range for this weapon is double this range. Weapons that have a range of “Close” means that they can only be used in hand-to-hand combat.

- Stun(X) is a special attribute reserved just for weapons that stun. X is the aptitude required to avoid a stun effect. If X is a trait (like Brawn) use the aptitude of the trait as the threshold. Some stun weapons also inflict Wounds, indicated by “+ #Wn” postfix.

| Weapon | Damage/Range |

|---|---|

| M16-A1 Battle Rifle | 5Wn @ 500m |

| AK-47 Battle Rifle | 6Wn @ 450m |

| M24 Sniper Rifle | 8Wn @ 400m |

| H&K MP5 SMG | 3Wn @ 200m |

| Glock 19 Pistol | 2Wn @ 50m |

| Remington 870 Shotgun | 6Wn @ 70m |

| M67 Grenade | Exceptional stun + 10Wn @ 15m |

| A Katana | 6Wn @ Close |

| Combat Knife | 3Wn @ Close |

| A Bat | Stun equal to Brawn + 1Wn @ Close |

| Fist or Feet | Stun equal to Brawn @ Close |

5.2 Protection

The start of any good plan is protection. Like the weapons list above, we only list the essentials: how many wounds this piece of armor can stop and how much it weighs.

- #Wn is just the number of Wounds this piece of armor will stop per hit. 8Wn means that the armor will stop up to eight Wounds per hit, but remember, each time armor soaks up trauma it loses a point of protection.

| Armor | Armor Rating/Weight |

|---|---|

| Class IV Kevlar Armor System | 8Wn / 8kg |

| Class IIIa Kevlar Vest | 6Wn / 4kg |

| Class II Kevlar Vest | 4Wn / 2kg |

| Full Plate Armor | 8Wn / 34kg |

| Chain-mail Armor | 4Wn / 11kg |

| Leather Armor | 2Wn / 6kg |